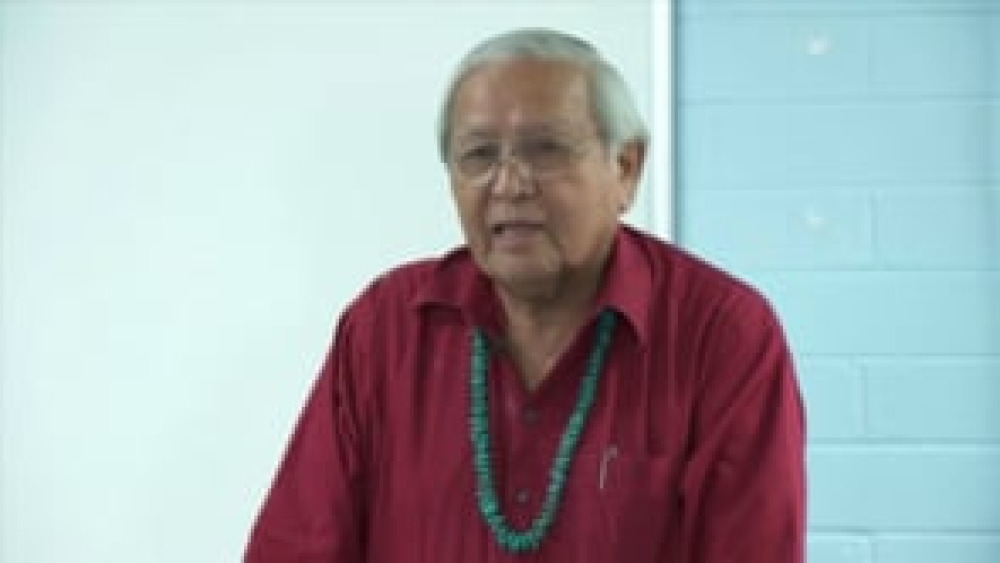

Former Navajo Nation President Peterson Zah shares the personal ethics he practiced while leading his nation, and discusses how he learned those ethics from his family and other influential figures in his life.

Additional Information

Zah, Peterson. "Addressing Tough Governance Issues." Emerging Leaders seminar. Native Nations Institute for Leadership, Management, and Policy, University of Arizona. Tucson, Arizona. March 26, 2009. Presentation.

Transcript

"Good morning. (I don't want to swallow this. It's so small.) I wanted to thank Steve [Cornell] for the introduction. I also wanted to give you two views about ethics. One of them is the written laws that your tribe may have, certainly with ours we do have that. And those are rules and regulations that governs the conduct of people who are elected to be responsible for your tribal government. The way I look at that is that that's a white man's law. It's in black and white and it has to deal with drugs, alcohol, conflict of interest, nepotism and those kinds of things. I always look at that law as, it's law written for the people that don't really have ethics of their own that's in their heart and it's in their mind that was given to them by their traditional people. They never really had that upbringing that they had, for example, with my coming from a highly traditional Navajo family and that's built into the tradition. So that is something that the Navajo Nation has. And then the second portion of the small presentation here is going to deal with the tradition, your own personal ethics. We each have that and you're the only one that knows that. To talk about it and how important that is in governance, in governing your people and governing a lot of the activities that go on in your nation. And so that will be my second presentation. However, I'd like to tell you a little story before I start.

Yesterday, as I understand, you were introduced to some of the Native American students that came from Arizona State University. And just indicate that the Navajo people love their children so much. And they are one of the groups of minority that I know of that really emphasize education, how important that is in life. And I guess because of that, we have today over 10,000 Navajo children that are going to colleges and university, supported by the Navajo Nation government through a scholarship service, supported by their own families, supported by many of the other entities that provide scholarship out there for Native American students and then many of them supporting themselves because of the traditional family instilling into them how important education is, what they can acquire during their lifetime. So that tradition lives on at ASU and we never really do things without our children. So I just wanted to congratulate Michelle [Hale] for continuing those traditions by bringing down some of these students that you met the other day. And you have to do things with your kids, with your children. You have to bring them on, bring them along, you have to educate them by example and by hearing a lot of these discussions that we have here today. And so I also just wanted to congratulate and welcome the students that we have here from Navajo and Apache.

The story is this: I got elected in 1983, and something like three or four days after the election I went back to my family in the center of the Navajo Nation called Low Mountain. We were in effect really celebrating among our own family members, my sisters and my brothers and my dad and my mom, aunts, uncles and grandmas and the grandpas were all there. And in the morning we had a lot of discussion, discussion around issues, politics, who all voted, how many people voted in that community of Low Mountain and all of that. And my dad at that time was about 85 years old. He could hardly walk, but he loved to herd sheep on horseback. So every morning, he would get his horse and he would saddle up his horse and then he let the herd out and then he came along on horseback to herd sheep. He says, ‘I'm doing this because I can't walk. I'm not as strong as I used to be and I can't run when the sheep tries to run off in the distance and so I have to have a horse.' But when he got on his horse, he wanted to pick up something that he had forgotten. The night before we were involved in local politics at Low Mountain, the discussion of how many people voted. And there was only one guy, one vote from my community that vote against me, that voted for the other party. And everybody was talking about who might that be. We were all discussing. In the morning my dad got on his horse and he also was talking about three or four days before there was a coyote that came into the herd and by god it killed one sheep and he was really ticked off about it. So brothers went over to the trading post, they got him some bullets and he had one of these 30/30 rifles that he always kept and it was always in his room. Well, he got on his horseback and he came to the front door and he says, ‘Gilbert, I forgot my rifle. Can you go get it and make sure that you also give me some bullets?' And my sister came out and she said, ‘Oh, you're going to finally kill that coyote that killed one of our sheep.' And my dad said, ‘No, I think I know who voted against us.'

A sense of humor is also very, very important as we discuss ethics, because when people violate certain ethical behavior expected of you or they violate the standard of conduct, it's a sad, sad thing. And my dad always had this sense of humor that was extraordinary about him. He was a member of the Navajo Nation Code Talkers, a trained code talker. And one day when I was just a young man way back in the early '40s, he told a story about how he was being taught to use the language. And he says, ‘When I go back and I'm having this furlough on a vacation in effect for the next two or three weeks and to spend the time with all of you. And then when I go back to San Diego, we're going on a ship and we're sailing to Japan. And we're going to be on the front line in combat using our language as Navajo Nation Code Talker.' So he, we had a ceremony and a sing and the medicine man painted him and all of that, did some prayers and he went back into the service. We said our goodbyes not knowing what the war may bring to [this] individual. But we were so surprised that a month later he was back. So I asked him and I said, ‘Dad, what happened, you're supposed to be in the war?' He says, ‘Oh, don't you know that Japan surrendered?' He says, ‘They knew I was coming.' A sense of humor in talking with groups of people in Navajo culture is very, very important, and it also has to do with ethics. So I wanted to just tell you that story.

Now, something about white man's law. Those laws are being enforced as we set it up in 1983-84. Because the courts were so overloaded with cases, we decided maybe the best thing to do is create a committee of the council that would get all of those ethics complaints that the Navajo Nation gets; that it would be the eight members that would act as a court, as a judge, as a forum where people can take their complaint to hold those hearings. And so basically the Navajo Nation has that system and people are encouraged to file these complaints with the ethics office. And when I checked last week about how those are going and how they're being handled and what are some of the most prevalent cases that we may bring to your attention -- and I do this because I want you to avoid them as much as possible -- on the Navajo Nation, the number one complaint is financial malfeasance or misfeasance, misuse of money. And that is happening because the Navajo Nation has decentralized its government.

We have on the Navajo Nation a government with over 300,000 people, 17 million acres of land and 110 chapters, local units of government. The Navajo is highly centralized and it has [an] 88-member council. So what the Navajo government did is they passed a law called the Local Governance Empowerment Act and that gave the chapters some authority, given to them by the Navajo Nation government, and they exercise those authorities at the local level to do what needs to be done. Along with that act, they also gave them some resources, some money to administer and that's where a lot of the misuse occurs. We also have 138 schools with 72 or 75,000 Navajo children going to school. So you have school board members, superintendents and principals that have all those duties to run those schools out there. There's a lot of misuse, misappropriation of funds. So it's the ethics office that handles those for the Navajo Nation. So number one is the financial malfeasance.

Number two is the conflict of interest. You all are familiar with that conflict of interest, where you have to avoid the conflict, where you have to not only avoid the conflict itself but every appearance of conflict you have to avoid because people interpret that a little different. And there's also a hazy area: what is meant by conflict of interest? I served on Window Rock High School Board for about, oh, maybe 12 years in my younger days. And every time a relative's contract would come before the board I always left the school board meeting either completely -- not participate in the discussion, particularly the voting -- or I went outside and took a smoke with some other guys in the community as it was being discussed; then coming back. That is a responsibility of the elected official to tell your colleagues that, ‘There may be a conflict here for me. So I'm going to try to avoid it by being outside. And you can always call me back in when you guys are finished with it.' The best way to avoid those is you yourself have to do that. So conflict of interest is high on the list for cases that are being handled by the Navajo Nation, the Ethics and Rules Committee.

The next one for Navajo is also very high, nepotism. You all heard about that, right? Nepotism, because we all say we're related to each other by clan. So the law has to be very, very careful in terms of how it states it and then how they enforce it because on the Navajo everybody is related to you. Everybody is related to you, especially when you get elected. They all come to you and they say, ‘I am your cousin or I am this,' and all of that. And so nepotism is one of those, like a conflict of interest case that's sometimes very hard to handle. Sometimes the courts can't deal with all of it. If we were able to put all of these things in court, our courts would be just loaded up with these kinds of issues. And so we try to have the local Navajo Nation government committee handle all of that.

And the last one that we have to deal with very carefully -- and there's a lot of that -- is courtesy to the employees. The elected officials misusing their power by the fact that they're members of the council and members of this committee using that authority and power and forcing an employee to do something that they shouldn't be doing. That's also high on the list of those cases being heard by the committee. And so we should as tribal leaders avoid all of this as much as possible.

I took office on the Navajo Nation in 1983 and we were in a terrible, terrible situation where the people or the person that I was running against was tried in federal court twice over misappropriation of money. And when your leader, the top guy, does that, then all of your other officials, their fuses go haywire; they want a part of the action. So when that happens, you have a complete breakdown of tribal government organization and function, especially when it comes to ethics; terrible, terrible problem. And that's what we faced when we went into that office. I even had people came to me when I first went to the Navajo Nation as chairman, some of the first few days where people were lined up outside -- Peabody Coal Company and all these other businesses that do business with the Navajo Nation. They wanted and they were expecting the same kind of favoritism that was given to them by the other tribal leaders.

I even had a guy come to me and he says, ‘Can you take a minute or two? I'd like to measure you, your arm, your chest, how tall you are.' And I said, ‘Why? We're here to talk business. Why do you want to measure me?' And the guy says, ‘Well, I think you'd look really, really sharp if you had a good suit on. If you had a blue striped suit with a nice necktie you'd look real sharp.' And I said, ‘Oh, my god.' I said, ‘You know, I like this and I like the way I dress. There's nothing wrong with it. It has nothing to do with my mind.' And he said, ‘Well, maybe the next time you're in Denver you can stop by and see us because we want to make you look nice.' [It was] very tempting because I didn't really have any decent clothes to wear, but my traditional family always said, ‘Be who you are. You're a traditional person by nature.' And that always come to mind when there were people who wanted to bribe you because that was the normal way of doing business in Window Rock. And so I wanted to just tell you and that's the standard of conduct that was issued by the Navajo Nation.

The next one is your own personal ethics. We each have our own personal ethics that was given to you by your tradition, by your families, by your grandmas and your grandpas. And you have to live by those; you have to live by those. Not only that you should know about it, and a constant reminder that that's what your traditional people taught you, but you have to live it, you have to be committed to it and you have to really practice that, because the only thing you have after leaving that office is your reputation. Yes, it was nice when I was in office because I had all these resources to help people with. But, when you leave office you don't have all of those resources. You have just you. You have just you. I am probably enjoying the best part of my life right now because I didn't commit anything and people know about it. You'll be surprised how many people follow your careers. They know about every little goof that you made, but they have a lot of respect for you if they never read bad things about you or never heard anything that's terrible about you. I'm really enjoying that right now because everywhere I go people respect the way you live. On the Navajo Nation with all of that money, I always tell people, I said, ‘See these five fingers, ten fingers. Millions and millions of dollars went between those fingers and not once did I put a dollar in my pocket. That belongs to the Navajo people. That belongs to your constituents.' I tell my friends, even in my own house. Yesterday I was driving this way to come to this conference, in my garage I saw a quarter and my wife says, ‘Hey, there's a quarter here.' And I said, ‘I'm not going to pick it up. That's not mine. That's not my quarter. It may be my grandson's, but whatever it is, it's not mine.' So I left it laying there. It's somebody else's quarter in my family. So you have to really, really practice those traditions when you go into govern your people and I think that's a very, very valuable thing to keep in mind.

I probably had the best teacher when I went into become a tribal chairman. There was a lady named Dr. Annie Wauneka. You probably heard some about her, probably read books about her. And she did some wonderful things in her life for the Navajo people. She was probably the best teacher. She always taught me these values. When I first decided to run, she said, ‘I'll support you. I'll go wherever you go.' So I would go to my first campaign rally at the chapter house. Boy, I would talk about my degrees. ‘I'm an educator, I got my degree from the university, I had these experiences, I was a legal service director,' and all of that. On the way back home after that rally she says, ‘My god, don't talk about that.' She says, ‘Don't talk about that. We, the Navajo people, don't value all of those things as much as maybe you do.' I said, ‘What do you want me to talk about?' She said, ‘Talk about your clan. Talk about your grandma, your grandpa. Talk about the fact that you were raised in the hogan. Talk about your corral where you keep your sheep. Talk about your dry farm and your field where you plant your corn and your beans and the squash -- all of those things that your family plants.' She says, ‘That's self-sufficiency; you don't rely on anybody else except yourself to live a decent live, a good life. Talk about your values, Navajo values. Not your master's degree, no.' That was Annie Wauneka trying to teach somebody who [she] thought was electable, but he just needed to say things a little more differently. So I probably do a lot of those things that my mother, my grandma, grandpa and what Annie Wauneka stood for. And those all had to do with ethics. One of the other things that Annie Wauneka said was, ‘Don't take things that don't belong to you. Don't ever think that it's nighttime. Nobody will see me. There's no one around. It's nighttime.' She says, ‘The night is your cheii'. The darkness is your grandfather. The people who are no longer with us, they turn into these great spirits and so your grandfather may be the night. You'll be taking things in front of your cheii', your grandfather. So don't you ever think it's dark time. Nobody's seeing it and so you're doing these crazy things.' Good lesson from a traditional person.

So my contribution to you today as young leaders, emerging leaders, is to live by those principles that have always been taught to you at a young age. And you'll be surprised at the end of your life, towards the end of your life how important those values are. Live by it, practice it. [Navajo language] Thank you."