Produced by the Institute for Tribal Government at Portland State University in 2004, the landmark “Great Tribal Leaders of Modern Times” interview series presents the oral histories of contemporary leaders who have played instrumental roles in Native nations' struggles for sovereignty, self-determination, and treaty rights. The leadership themes presented in these unique videos provide a rich resource that can be used by present and future generations of Native nations, students in Native American studies programs, and other interested groups.

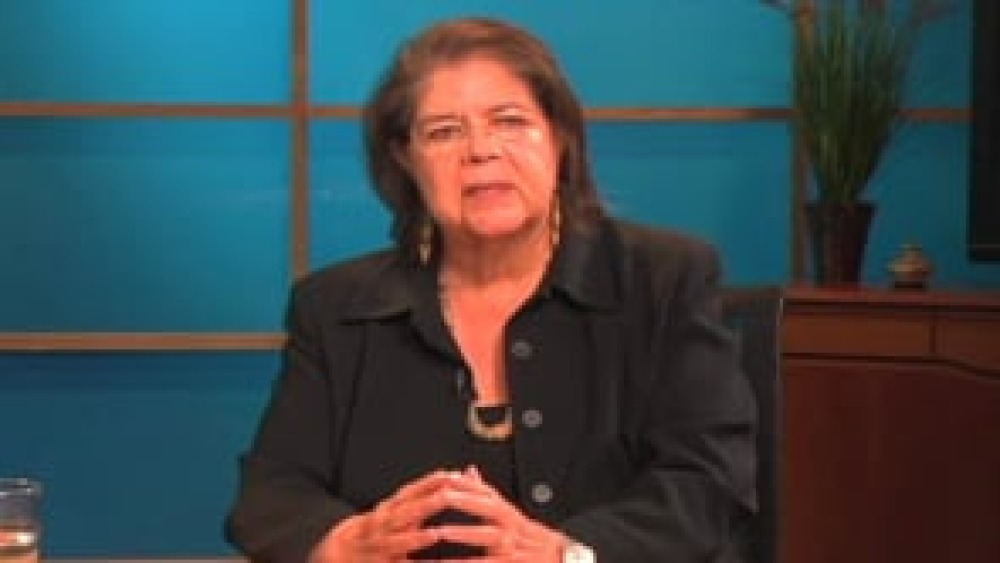

In this interview, conducted in July 2001, former Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation Wilma Mankiller traces her ascendancy from a child of the termination and relocation policies of the 1950s to becoming the first female elected to serve as principal chief of her nation.

This video resource is featured on the Indigenous Governance Database with the permission of the Institute for Tribal Government.

Additional Information

Mankiller, Wilma. "Great Tribal Leaders of Modern Times" (interview series). Institute for Tribal Government, Portland State University. Tahlequah, Oklahoma. July 2001. Interview.

Transcript

Kathryn Harrison:

"Hello. My name is Kathryn Harrison. I am presently the Chairperson of the Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde Community of Oregon. I have served on my council for 21 years. Tribal leaders have influenced the history of this country since time immemorial. Their stories have been handed down from generation to generation. Their teaching is alive today in our great contemporary tribal leaders whose stories told in this series are an inspiration to all Americans both tribal and non-tribal. In particular it is my hope that Indian youth everywhere will recognize the contributions and sacrifices made by these great tribal leaders."

[Native music]

Narrator:

"Wilma P. Mankiller, former Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation, was the first female in modern history to lead a major tribe. Mankiller was born in Tahlequah, Oklahoma, in 1945 and today lives on the land allotted to her paternal grandfather in 1907 just after Oklahoma became a state. The family name, Mankiller, she explains is derived from the title assigned to someone who watched over Cherokee villages, a kind of warrior. Wilma Mankiller herself is a protector of her people and a kind of warrior for justice. Her goal as a community organizer and leader of the Cherokee Nation has been to help bring self-sufficiency to her people. Most of Mankiller's childhood was spent close to the land and in strong relationship with other Cherokee people. In the 1950s the Bureau of Indian Affairs encouraged the family to move to San Francisco under the Bureau's relocation program. The adjustment was extremely difficult for the Mankiller children but Wilma Mankiller was later able to benefit from participation in the social reform and liberation movements of the 1960s. She was inspired by the events of 1969 when a group of students occupied Alcatraz Island to bring attention to the concerns of tribes. Also in California her understanding of treaty rights and tribal sovereignty issues was deepened when she worked with the Pit River Tribe. Mankiller returned to her ancestral home in Oklahoma in the early 1970s. Her ideas for development in historic Cherokee communities caused Chief Ross Swimmer to take note of her work. Mankiller's work was interrupted by a near fatal accident and 17 operations. But through near-death and convalescence she emerged renewed and even more dedicated to work for her people. Chief Swimmer convinced Mankiller to run as his Deputy Chief in 1983. When Swimmer resigned to head the Bureau of Indian Affairs in Washington, Mankiller assumed the duties of Chief as mandated by Cherokee law. She was strongly opposed by tribal members who did not want to be led by a woman. She ran for Chief on her own in 1987, was elected and ran and won a second term. Wilma P. Mankiller has made a great impact on her own people and other Americans as a tribal and spiritual leader. She received the Ms. Magazine Woman of the Year Award in 1987 and to her great pride one of the health clinics that she helped found bears her name. In 1998 President Clinton presented Mankiller the Presidential Medal of Freedom. In an interview conducted by the Institute for Tribal Government in July, 2001, Mankiller spoke about the historic struggles of the Cherokee people, her development as a tribal leader, her battles to win the post of Chief and the important issues for tribes today."

The Cherokee people

Wilma Mankiller:

"In 1492 we were in the southeastern part of the United States in North Carolina, Georgia, Tennessee, a little part of Virginia, a little part of Alabama and the whole southeast. The Cherokee people I think went through a lot of different phases and a lot of different discussions about how to relate to their new neighbors. Certainly like every other tribe in the country we were forced into treaties where we always ended up ceding land and eventually lost a lot of land in the southeast just through treaties and through war and many other events. But at different periods we were at war. At other periods we had an official policy of almost accommodation where we tried to figure out how to get along with our new neighbors and whether we were in a war era or whether we were in an era of cooperation. It didn't matter, we lost our land and lost many of our rights anyway and so no matter what our official policies might have been."

The Cherokee Nation rebuilds itself after repeated injustice and assault

Wilma Mankiller:

"One of the most famous stories among the Cherokee is that when Jackson was a soldier and fighting one of the major battles that a Cherokee person actually saved his life, a Cherokee warrior saved his life and he lived to regret that. Later Jackson made his reputation as an Indian fighter and as a military man and then later when he became President, almost one of the very first acts was to try to convince the Legislature to pass the Removal Act, which eventually resulted in the Cherokees being dispossessed of their land in the southeast. Most people refer to the Cherokee removal as the Trail of Tears or the Trail Where They Cried because of the large loss of land and large loss of lives but actually all the tribes in the southeast went through the same sort of removal process. The Choctaws and the Creeks and the Chickasaws, the Seminoles, many other tribes went through the same situation. Our story I think is just the one that's more familiar. Our land where we had lived forever was given away in lotteries to White Georgians after the Cherokees were removed and this land's very different in Indian Territory than the land in the southeast. The political system, the cultural system, the medicines, the life ways, everything we'd ever known was left behind so our people arrived here with everything in disarray. Many people dead, everything familiar gone and yet what's absolutely remarkable about Cherokee people is that they almost immediately began to reform the Cherokee Nation and rebuild their families and rebuild their communities and rebuild a Nation and it's just absolutely amazing that they were able to do that given what had just occurred. So everybody helped each other. Most people were farmers and had small animals and they lived basically on a barter system where they...if one had eggs they would trade them to somebody else for milk or if one grew corn they would trade them to somebody who grew tomatoes or that sort of thing. People had a strong sense that if they were going to survive they had to rely on each other."

Life as a child at Mankiller Flats, family, community, connection to the land

Wilma Mankiller:

"My father was a full blood Cherokee who went to...attended boarding school. In those days when my father was a child they took children without permission from the parents. They literally came out and picked...to this community and picked up my aunt and picked up my father and took them to boarding school. A lot of people have stories about losing their language in school, in boarding school but my aunt and my...neither my aunt nor my father ever lost the ability to be very fluent in Cherokee. I think in part because they had each other to talk to. He had a lot of mixed experiences at boarding school but the one thing that he learned at boarding school was he learned the love of reading and of literature, which he passed on to his children. My mother is as best we can tell she says she's Heinz 57 varieties but she's Irish mostly and a little bit Dutch. She is also from this community. She went to probably maybe the seventh grade or something. Very well read, very politically astute. I guess she's what everybody would want for a mother. She is always steady, always gives her children unconditional love. My brother went to Wounded Knee and her advice to him was, ‘Well, just don't get shot.' It was mostly a life of a relationship with the land because we had a large family and a small house and no electricity or indoor plumbing or any other amenities and only one person several miles from here had a television. So our life was really very centered around the land. And we all took turns gathering water from the spring for household use and for consumption. It was the same spring that my grandfather had used and my father had used and so there was a sense of connection to the place and to the land. And so when I think of my childhood I think mostly of being outside and having a very close relationship with the land."

The family relocates to San Francisco in the 1950s

Wilma Mankiller:

"I think the Bureau of Indian Affairs basically told my father that he could have a much better life for his children if we moved away. And it seemed like a way to make sure that we were provided for and all that. That was the main sales because at the time we couldn't conceptualize a world beyond Muskogee. We'd been to Muskogee to the State Fair and to even talk about going to someplace like California was, we were unable to think about it in anyway. It would be like us sitting here saying, ‘I think I'll go to Mars,' and it was a world we couldn't visualize and couldn't imagine. We just knew that it was away from here and we'd have to leave home so we were not happy at all about that and in fact I asked my parents if I could stay here in Oklahoma with relatives. It was a very difficult time. I remember vividly the day we left on the relocation program, we're all piled in the car and headed to Stillwell and I sort of looked very carefully at everything to try to memorize it, the school, the road and everything else. And I always knew I would come back, even at 10, I knew that I would come back. We left a very isolated and somewhat insular world here, a very Cherokee world and got on a train and several days later we ended up in San Francisco with all the noise and confusion and everything else going on and we actually...the Bureau of Indian Affairs arranged for us to go to a hotel. I'll never forget, it was called the Keys Hotel in the Tenderloin District of San Francisco which is the Red Light District of San Francisco and we saw and heard things that were inconceivable to us. I remember my brother Richard and I hearing a siren and we could only relate that to what we knew so we thought it was an animal and we were trying to identify what kind of animal was making that sound. In fact I hated school ‘til I got to college. I couldn't stand school and found every opportunity that I could to avoid school because we were so different. We were country kids and we dressed like country rural people. We had the name of Mankiller. Children can be very cruel and so we were treated differently. We were immediately labeled as different and so...in school...so school became an unpleasant place. And as I got a little older we started going to the San Francisco Indian Center and that was the place where we met other people like ourselves who were from someplace else and just trying to figure out a way to...how to carve a life out in the city. And so that was extremely helpful."

Mankiller learns social issues from family: seeds of activism

Wilma Mankiller:

"There were always Indian people at our house and there was always discussion of what was going on in the world, what was going on in the communities and so eventually there were a lot of people who had ideas about relocation, which was really a very misguided policy and just about things in general. In terms of a political background or figuring out how to be engaged in the community I probably figured out how to do that just by listening to people at home. At the time I did not appreciate that. All I saw as a child and as a teenager is that dad would bring home people and my sister and I would have to give up our bedroom so these strangers could stay there but it sort of soaks in. Or dad didn't have money for us but he always had a $20 bill that he folded up and kept way in the back of his wallet that he would give to a family down on their luck. And so we would rather he had taken us to the beach or given us the money for the show and then later you realize that all that has an impact on you."

The family lives at Hunter's Point, an African-American community

Wilma Mankiller:

"And I still value that time because it gave me a close view of how an African community works from inside the community. There's a lot of strength and a lot of leadership, untapped leadership in African-American communities that nobody ever taps into and when people sit around and wring their hands about what to do about inner city problems, I think, ‘Why don't they just go sit down with the people and ask them?' In fact the first volunteer work I ever did was with the Black Panther party, which was again not like at that early stage not like the media portrays it but there were people who wanted to provide breakfast for elderly people and do a lot of...provide programs, a lot of really good things. And then in 1969 when Alcatraz was occupied, it was kind of a watershed experience for me and my whole family and four of my brothers and sisters moved over almost immediately to the island and helped out and so it was just an unbelievable period of time."

Mankiller discovers new strength from the Women's Movement

Wilma Mankiller:

"It was a marvelous time because before that I think we had like many women of my generation we had lived our lives through the men we were with and through our children and through other people, our lives were in response to somebody else, they weren't who we were and so we were always in a secondary role. We were...at the time I was doing work in the Native American community and I was the person who wrote the speeches for the men and arranged their press conferences, wrote the proposals and always tried to convince them that we should do one thing or another but never articulated my own ideas and so it was a time of awakening for us and kind of coming into our own."

Mankiller cultivates leadership skills directing a youth center in Oakland, attending San Francisco State University and working with the American Indian Resources Center

Wilma Mankiller:

"I gained skills on how to run a youth center period. I had no idea when they offered the job to me what it entailed. You had to develop curriculum, hire teachers, find the building. I thought, ‘Oh, this'll be a neat job.' Well! Anyway, so I ended up having to locate the building, find painters, fix it up, develop a curriculum and I loved the job. It was an inner city street after school program really and it was called the Native American Drop In Center. And all the kids would come after school to be there and work on their homework or have recreation and we did all kinds of things to help them feel good about themselves. At the time there was a Mescalero Apache singer named Paul Ortega who was making the rounds and so we had his music playing all the time and Jim Pepper, a Caw musician and other people like that to show them some role models, Native American role models. We taught the girls how to make shawls and taught the boys how to dance and drum, lots of things like that. It was fun."

Mankiller works with the Pit River Tribe in Northern California

Wilma Mankiller:

"Well, I think I was inspired at Alcatraz, by what had happened at Alcatraz to be more involved in things around me and I actually saw the Pit River Tribe on the evening news and they reminded me so much of people here. They were rural, Native American people who seemed familiar and so I called up their lawyer who had done an interview on the evening news and I volunteered to do some work for them, whatever they wanted me to do. And so mostly I worked as a volunteer at the legal offices in San Francisco but I spent a lot of time with Pit River people on their land and learned a lot. They were the first group of people I worked with who framed Native American sovereignty issues in an international context and saw the issues as international issues and not just national issues. So that was very helpful for me. I learned a lot about treaties, the treaty rights and the relationship between the federal government and tribal governments during that period at Pit River and in part because I worked for them as a volunteer at the legal offices and I've also helped them put together their history books and various things like that. But I learned a lot just sitting on the porch of some of the elders there at Pit River and I still have a very vivid image of these older people, Charlie Buckskin and Raymond Lague going and finding this little precious box of old papers, which supported their claims to their land near Mt. Shasta. And they treated those papers almost like they were sacred objects because it was their claim to their homeland. So that was a wonderful experience for me and my association with them was for about...until I left, until probably the mid ‘70s I was associated with them."

Mankiller balances life as a single mother, as a student and activist

Wilma Mankiller:

"I don't think that I balanced it very well for most of the time I was doing all that. I think that I had a singular focus on getting things done and so I just did the best that I could under the circumstances. My children went with me wherever I went. My children went to meetings, my children went to Pit River; whatever I did my children did those things with me. I co-founded a Freedom School in Oakland while I was there along with other Native American people and my children, I took my children out of public school for well over a year and they went to school in the Freedom School. Whatever I was involved in they were involved in."

In the mid 1970s Mankiller decides to return to Oklahoma

Wilma Mankiller:

"I think that part of the decision had to do with wanting my children to experience being part of a Cherokee community, part of it was that I wanted to do more local work and wanted to work with my own people. I had helped gather documentation for the 1977 conference in Geneva on Indigenous Rights and so I was dealing with very lofty principles of international law as they relate to Indigenous people and that's all well and good and certainly that work needs to be done but it was hard to reconcile that work with coming home and finding kids sniffing paint and people needing housing and needing healthcare."

Mankiller begins work with the Cherokee Nation in 1977

Wilma Mankiller:

"Basically I recruited Native American students from around the state for environmental training at a small college near Oklahoma City. When I took the job I had no idea where Midwest City was or where all these other tribes in Oklahoma were situated or anything. I hadn't been home that long but I thought, ‘I can figure it out.' And by the time I got processed and onboard it was early November of '77 and I had to recruit students for the spring semester beginning in January but I did it. I got the students there and did what I was supposed to do. Well, I sort of kept moving up. I started writing on my own, grants for the tribe and for projects and I've always liked writing and liked development and so then I moved into a development position and then eventually moved from the field office to the main office and moved into planning and then ultimately ended up doing community development work."

Chief Ross Swimmer moves Mankiller to tribal headquarters

Wilma Mankiller:

"Well, I had pitched to him before he started doing community development the idea of doing more work in communities like mine which is a rural Cherokee community. And the people who seemed to me to be getting the most services from Cherokee Nation were people who knew how to work the system and who had the ability to get to the Cherokee Nation. By and large they were many more mixed blood people than full blood people who knew how to get around and get things done and were much more pushy. And people in communities like mine were not getting served. And so I had written a paper, co-written a paper with a colleague at work and pitched the idea of doing work more in historic Cherokee communities. And so that...when he started thinking about doing community work I came to mind because of the paper I think."

Cherokees in small communities

Wilma Mankiller:

"I think they felt and I think they continue to feel a sense of alienation from the tribal government because the current system of tribal government that we have and which I was elected to bears little resemblance to our original way of doing things and the original way of doing things was that tribal communities had a great autonomy and their own leadership and there was no single leader or set of leaders who had unilateral authority over all the people. And so the only time all the Cherokee villages came together was probably in times of great catastrophe or an external threat and there was great respect for the local community leadership. And so Cherokee, the Cherokee Nation, like many tribes that have a form of government that's no longer their traditional form of government, have relatively low voter participation because people see the government as a place to go and get services but not the government in the sense of it being an integral part of their family or their community."

Mankiller's life is transformed by a series of events beginning in 1979

Wilma Mankiller:

"When I came home, I didn't come home and necessarily enter the world of the Cherokee Nation and politics. I came home to the traditional Cherokee world and I guess I'd missed it and I guess I didn't feel whole without that so I spent a lot of time going to stomp dances, I spent a lot of time with my uncle who's now passed away who led a ceremonial dance, a stomp dance, and my world was very different and my view of the world was very different. And so I saw the world from a different perspective and in that world disagreements were settled sometimes by medicine. There was good medicine where people could heal each other and provide comfort in times of stress or trauma or heal an illness and that sort of thing using traditional medicine. And there were also people who could use negative medicine to harm people. And during that period of time I learned from traditional Cherokee people that there were certain signs, if you were quiet and looked for signs that there were signs that you could see of an impending disaster or like a warning or something. And one of the things that they told me was that owls were messengers of bad news and so I became kind of leery of owls. The night before something really bad happened to me, two of the people who were part of what was my world then, a guy named Bird Wolf and his wife Peggy who are both full blood Cherokee people who are very involved in the ceremonial grounds came by to visit. And we spent the evening talking about, in part about the extent of which Cherokee medicine still had a huge role in the life of Cherokee people. And it was really interesting because that night that they were here we had...the house became surrounded by owls and in a way that it's just even hard to believe today that this happened because it was not the kind of behavior I've ever seen before and rarely heard of. But the owls actually came up to the window and they were everywhere, all over, and it was really very frightening. But I didn't connect that with anything going on in my life, it was just kind of a frightening situation."

In a head on collision with a car driven by a friend, Mankiller survives but her friend does not

Wilma Mankiller:

"And I remember briefly seeing the car, of course not seeing her but seeing the car, and then I didn't wake up for several days. But what was interesting and life changing is that I came so very close to death during that head on collision that I could actually feel it. I know what it feels like and it's actually very enticing and at the time I didn't know anything about near death experiences or hadn't read anything about them and so I didn't see a light or a lot of things the other people see during that period of time but I felt bathed in the most wonderful unconditional love and I felt drawn toward death. It was like this is what I lived for, everything I'd ever lived for and it was the most emotionally all-encompassing feeling that I've ever had. And I remember during that period of time when I was moving toward that feeling and was going to settle there that an image of my children, Felicia and Gina, who were young and I...that image sort of called me back and pulled me back from going there and staying there. So I think that had a profound impact on me, just the fact that I no longer, when I came out of that experience, I no longer feared death and so I therefore no longer feared life. So in a way I think because of some thinks that happened to me after that, I think that that accident prepared me for what was to come because I came out of that whole experience a different person."

Mankiller and Charlie Soap organize the Bell Community Project

Wilma Mankiller:

"Bell Community is not unlike other Cherokee, historic Cherokee communities. It was probably 85 to 87 percent of the people were bilingual. It was considered to be a rough community, a very troubled community. The school was in danger of closing cause so many young families were leaving. They had no water, no central water line. About I would say 25 percent of the people in the community had no indoor plumbing. There was a need for new houses. There was a lot of dilapidated housing in the community; very few services or programs. Many people weren't even enrolled in the Cherokee Nation tribal government and so anyway they wanted housing. In order to get housing they needed water and in that community it made more sense to do a water line. And so the Chief wanted to try to do a self help project there and so Charlie and I facilitated that process. And so the Chief and Charlie and I basically were probably the only three people who believed that people would actually rebuild their own community. So anyway we got the community together, we worked for them. They organized a steering committee with local leadership, elected from every single corner of the community and planned their own program with us as the facilitators. We just kind of kept a timeline and brought resources when we needed to, an engineer to design the system, funds to pay for the material, developed a system for organizing the labor so that it was done in a consistent way. And at the end of probably a little less than a year we finished...they finished an 18 mile water line using volunteer, totally using volunteer labor. Women worked and men worked and every family was represented."

Chief Swimmer asked Mankiller to testify for him before Congress

Wilma Mankiller:

"He had more confidence in me than I had in myself. Oh, my god, I had no idea where I was going, what I was doing and everywhere I went...I went to testify before a committee for the Chairman Yates was presiding over and after I finished my stumbling testimony he said, ‘Where's Ross Swimmer?' But, my goodness, my first trip was a disaster. It got better after that but he certainly had a lot more confidence and I'm sure he got lots of phone calls saying, ‘Who is this woman?' And then he asked me to represent him at various meetings and that sort of thing when he was ill as well."

Chief Swimmer asked Mankiller to run as his Deputy Chief

Wilma Mankiller:

"Initially I said no because I couldn't imagine myself making the transition from a community organizer and kind of a social services person who was a little bit bookworm-ish to a politician and our tribe's a very large tribe and elections are real mainstream kind of elections with...during that time they used some television, a lot of radio, a lot of direct mail. I just launched my own campaign, completely separate campaign without knowing anything about it but I used my own money and bought ads and did a lot of things to get myself elected."

Mankiller deals with resistance and hostility during her campaign

Wilma Mankiller:

"I tend to be a positive person and try to be very forward thinking and focus on the future. And there's a Mohawk saying that's probably my favorite saying that says, ‘It's very hard to see the future with tears in your eyes.' And so you can't spend a whole lot of time dwelling on negative things or crying about negative things or it blurs the future. So you have to kind of stay focused and keep moving forward. I think the accident prepared me for all that because it literally never touched me. I never saw their attacks as anything personal having to do with me. I saw them having to do with something going on with themselves or just a disagreement they had with me on an issue. I never took it personally and I think I was very fortunate throughout my entire political career that I was able to do that. I'm able to stay real focused on what I need to do, whether it's build a clinic or win an election. It's not about me, it's about a much larger issue and if I would have let my energy be drained off into thinking about me or my reaction to hostility, I'd have never got anything done and so I just didn't focus on it. I think that in any given political situation, people who put themselves out there to be elected know that there's immediately going to be a contingent of people who are very hostile, some overtly hateful who are going to be that way for reasons of their own that have little to do with me. And then I think people have a legitimate right to disagree with their leaders and so they have a right to have their own view of things."

As Deputy Chief, Mankiller heads the tribal council

Wilma Mankiller:

"Well, at first, because the entire tribal council had opposed my election they weren't real crazy about my being their president and so it took awhile to establish a relationship with them. And once they saw that I was going to be serious and focused and wasn't going to be drawn into games or negativity in anyway, that I was about the business of the tribe, I think they settled down and we settled into kind of a routine. And of course they thought the world would crash and burn when Ross Swimmer resigned two years after I was elected Deputy Chief to go head the Bureau of Indian Affairs and then I became principle Chief. Then they were just absolutely alarmed. So there were a number of threads running then. I think they one thought that things were going to be terrible for the last two years of Ross's term which I filled and on the other hand they thought, ‘Well, we'll just live through these two years and we'll defeat her in the next election,' which was the 1987 election. So it was a very difficult time because our constitution allows for the Deputy Chief to move into the Principle Chief's office if he resigns or vacates the office. If the council had had to make the decision I would have never been selected. They would have selected somebody else. So I was left with his staff, his mandate, a council that didn't support me and I had to figure out a way to get some work done in that situation."

Mankiller runs for Chief with the enthusiastic support of her husband and family

Wilma Mankiller:

"Charlie was very enthusiastic and very, very supportive of my election and I would not have won election without his support because he's very fluent in Cherokee and was able to talk to a lot of people who, older people and other people who would not I don't think had voted for me -- men -- a lot of people would not have voted for me had he not been able to sit down and talk with them in Cherokee and explain to them why I should be elected. So he was critical to my election. My whole family was supportive. My mom got out and put up signs and my sisters served as poll watchers so everybody was extremely supportive of me during that whole period of time.

Her priorities as Chief

Wilma Mankiller:

"When I came to the Cherokee Nation in 1977 as an employee there was almost no healthcare system. Our options were two Indian hospitals one Claremore Indian Hospital, the other one was Hastings Indian Hospital and being able to take the plans put together by tribal health staff and tribal members and make those plans real is probably the thing I'm most proud of. We basically were told by the people that we needed to decentralize healthcare and move it closer to the people. So during my tenure we built a $13 million clinic in one community, $11 million clinic in another community, we bought a hospital in still another community and renovated a building in another community and when I left we'd started another $10 million project in another community and so we built a lot of healthcare facilities that are closer to people. And the one in Stillwell in this town, our hometown, is named after me. The council...I was out of town and the council passed a resolution naming the clinic in this town the Wilma P. Mankiller Health Center, which is interesting given the fact, given how I started out with the council."

Relationships with other tribes

Wilma Mankiller:

"It would seem natural to me because I had been involved in the San Francisco Indian Center with many tribes and had done a lot of work among other tribes. Having relationships with other tribes seemed not only natural and normal but desirable. I wanted to know what they were doing and oftentimes some of the smaller tribes with far less resources than the Cherokee Nation were doing far more innovative than what we were doing at the Cherokee Nation. So I learned things from them, we shared information, we tried to support one another and help one another. And so I think that for some tribes I think they get a little tired of always hearing about the big tribes like the Cherokee Nation or the Navajo Nation and so there's a little bit of that but I think by and large there was a great relationship. The two times when tribes had to select people to represent them with President Reagan and with President Clinton and both times I was selected by the tribes themselves as one of the people to go and meet with the President. So was Pete Zah, my partner in a lot of this work."

Cherokee lands and environment

Wilma Mankiller:

"I personally had taken a hard and fast rule, pro-environmental rule so we weren't approached by a lot of people who would do damage to the environment so that was never a real huge issue for us. I think someone came once, you could always tell these guys that are coming from organizations that'll devastate the environment, they generally have a Rolex watch and a great spiel about how they can protect the environment and do all this stuff and so we would send them away."

During his lifetime, the great Chief John Ross revered the judicial system of the United States. Mankiller comments on the system today

Wilma Mankiller:

"I think I was less shocked than the rest of America by the Supreme Court's involvement in the 2000 election because I've seen how politicized the judicial system can be. We're very fortunate in the 10th Circuit in Denver for our region to have I think a pretty fair set of judges but that's certainly not the norm. I think that I've come to understand how very political the justice system is and you can simply look at the number of Native American women and men that are in prison and the number of Black men and Black women that are in prison and look at, compare that to White people who have committed similar crimes and understand a little bit about the judicial system in this country. And so I didn't have...I don't think I had the blind faith that other people had and I've never had the optimism that John Ross had that the judicial system was indeed just. So I wasn't shocked by what the Supreme Court did at all, not at all. I think it's significantly diminished the stature of the Court in the eyes of most Americans."

What progressive people can learn from opposing forces

Wilma Mankiller:

"Well, I'll tell you, the right wing has certainly figured out how to organize families and communities around the issues that are important to them and I think that people on the left in the ‘60s let the right just walk away with issues around spirituality and religion and a lot of other family values and they practically turned religion and spirituality in a bad word because they have such a narrow interpretation of...the right has such a narrow interpretation of religion and spirituality. I think we have a lot to learn about how they listened to the people then organized around issues that are important to everyday people. I think there's that lesson. For me, because I live in a state that's very conservative and there are a lot of right wing people, I'd rather deal with up front, right wing people than I would these squishy liberal people who are just as racist, just as greedy and are just as unsupportive of Native American rights who will read these wonderful stories about Chief Seattle and quote him in their meetings but who wouldn't lift a finger to help tribes and tribal sovereignty issues or tribal rights or who would not stand with Indian people in times of trouble. Give me an out and out racist any day than someone who will have the liberal chatter at a cocktail party and have more of a smoke and mirrors way of doing the same thing."

Interdependence and our responsibilities to the earth

Wilma Mankiller:

"What I mean by interdependence is I think that the Creator gave Indigenous people ceremonies to help us understand our responsibilities to each other and the responsibilities to the land and I think that the original instructions we were given as Indigenous people are what keeps us together as a people and that everything's connected to everything else. And so to me a life is not worth living unless you're engaged in the community around you, unless you have some sense of interdependence with other people and with the land and so when I speak of interdependence that's what I speak about. I think that the message we hear on television and magazines and films about doing for yourself and only thinking about yourself and that sort of thing, I think we should reject those messages and remember that we have a responsibility to each other as human beings and we have a responsibility to the land."

Major challenges for tribes today

Wilma Mankiller:

"We have just a daunting set of health, education, housing and economic development problems but the central issue I think for people is going to be...the central question is going to be, ‘How do we hold on to a sense of who we are as Indigenous people?' We can't do that if we lose traditional medicines, traditional knowledge systems, any sense of connection to our history and to our stories and to the land. And we've lost everything if we've lost that."

The prophecy of Charlie and the two wolves

Wilma Mankiller:

"Since almost the time of contact the Cherokees have debated the question of how to interact with the world around us and still hold on to a strong sense of who we are as Cherokee people. And the question became more confusing and more difficult as Cherokee people began to intermarry with Whites. And so at some point in history Charlie the Prophet appeared, a Cherokee man appeared before a meeting with two wolves and he warned the Cherokee people that they would die if they didn't go back to the old ways, the old Cherokee ways of planting their own food and living according to the old values. And I keep that statue and I have also a poster in the hallway of this same prophet to kind of remind me that it's an ongoing and continual debate among Cherokee people. How do we hold onto a sense of who we are as Cherokee people and still interact with the society around us? And I think that Charlie the Prophet when he was talking about the Cherokee people would die if they didn't go back to the old ways, he wasn't talking about physical death, he was talking about a spiritual and a cultural death and so I think his message is an important one that if we're to survive as tribal people and enter the 21st Century and beyond that the single most important thing we can do is to find a way to hold onto our culture, hold onto our life ways, hold onto our ceremonies and songs and language and sense of who we are."

The Great Tribal Leaders of Modern Times series and accompanying curricula are for the educational programs of tribes, schools and colleges. For usage authorization, to place an order or for further information, call or write Institute for Tribal Government – PA, Portland State University, P.O. Box 751, Portland, Oregon, 97207-0751. Telephone: 503-725-9000. Email: tribalgov@pdx.edu.

[Native music]

The Institute for Tribal Government is directed by a Policy Board of 23 tribal leaders,

Hon. Kathryn Harrison (Grand Ronde) leads the Great Tribal Leaders project and is assisted by former Congresswoman Elizabeth Furse, Director and Kay Reid, Oral Historian

Videotaping and Video Assistance

Chuck Hudson, Jeremy Fivecrows and John Platt of the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission

Editing

Green Fire Productions

Photo Credit:

Wilma P. Mankiller

Clinton Presidential Materials Project

Great Tribal Leaders of Modern Times is also supported by the non-profit Tribal Leadership Forum, and by grants from:

Spirit Mountain Community Fund

Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs

Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde, Chickasaw Nation

Coeur d'Alene Tribe

Delaware Nation of Oklahoma

Jamestown S'Klallam Tribe

Cow Creek Band of Umpqua Indians

Jayne Fawcett, Ambassador

Mohegan Tribal Council

And other tribal governments

Support has also been received from:

Portland State University

Qwest Foundation

Pendleton Woolen Mills

The U.S. Dept. of Education

The Administration for Native Americans

Bonneville Power Administration

And the U.S. Dept. of Defense

This program is not to be reproduced without the express written permission of the Institute for Tribal Government

© 2004 The Institute for Tribal Government